The Colours Behind the Canvas

When visitors stand in awe before a Renaissance masterpiece, whether it is Raphael’s serene Madonnas, Michelangelo’s powerful frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, or Titian’s fiery portraits, they usually marvel at the composition or the dramatic interplay of light and shadow. Yet behind those breathtaking images lies something far more elemental: the very minerals of the earth. The pigments that gave these works their unparalleled vibrancy were not mass-produced paints from tubes (those would not exist until the 19th century) but rather powders ground from pigment stones, imported minerals, and humble earths transformed into enduring colours.

This hidden world of pigment stones connected the Renaissance not only to artistic craft but also to global trade, alchemy, and theology. Lapis lazuli mined in Afghanistan could travel thousands of miles to become ultramarine blue in a Florentine Madonna. Cinnabar dug from Spanish hills could blaze forth as vermilion in a Venetian altarpiece. Such pigments carried stories of distant lands, enormous wealth, and secretive knowledge.

What Are Pigment Stones? A Foundation of Natural Pigments

Pigment stones are minerals and geological substances that artists processed into finely ground powders to create colored paints. Unlike organic pigments derived from insects or plants, such as the red carmine made from cochineal beetles, mineral pigments offered distinct advantages: stronger hues, higher permanence, and more symbolic associations.

The process of creating a usable pigment from stone was labour-intensive. It involved crushing and grinding the mineral into an ultrafine powder, then mixing it with a binder. In tempera painting, the pigment would blend with egg yolk. In fresco painting, pigments were mixed with water and applied to wet plaster. And in oil painting, pigments were combined with linseed oil to create radiant glazes.

Mineral pigments were highly valued during the Renaissance for three main reasons:

- Durability: Unlike many organic colours that faded quickly, mineral pigments often retained their brilliance for centuries.

- Trade Value: Some, like lapis lazuli, were so rare they became luxury commodities, often more valuable than precious metals.

- Symbolism: Colours derived from stones carried natural associations; ultramarine as heavenly, cinnabar as fiery energy, green malachite as fertility and renewal.

Thus, pigment stones were not just materials but cultural symbols, bridging geology, art, and spirituality.

The Renaissance and the Language of Colour

The Renaissance, spanning roughly the 14th through 16th centuries, was more than a revival of classical art; it was a rebirth of colour’s role in human culture. Painters rediscovered the expressive and symbolic power of hues, experimenting with chromatic variety in ways that medieval art had not fully employed.

Colour in the Renaissance carried multiple layers of meaning:

- Social and Economic Value: Wealthy patrons expected the most luxurious pigments to be used for their commissions, both to honour the sacred subject and to display their own financial power. For instance, a patron might specifically demand ultramarine for robes, thus signalling their wealth and devotion at once.

- Spiritual Language: In a society deeply infused with Christian symbolism, certain colours signified divine truths. Blue represented purity and the heavens. Red embodied sacrifice. authority, and passion. Gold reflected divine light.

- Aesthetic Innovation: Renaissance painters, particularly after the introduction of oil painting into Italy in the 15th century, exploited pigments for new effects. With their rich glazes, glowing flesh tones, or atmospheric landscapes.

Thus, pigments were not only a raw material. They were tools of communication, with mineral origins lending them physical and metaphysical weight.

Iconic Pigment Stones of the Renaissance

Ultramarine: The Lapis Lazuli Legacy

No pigment encapsulates Renaissance splendour more than ultramarine, a vivid blue derived from lapis lazuli. This stone was mined primarily in Badakhshan, a remote region of Afghanistan. From there, torturous trade routes, often controlled by Venetian merchants, carried the prized mineral into Europe.

The preparation of ultramarine was painstaking. Artisans had to grind lapis lazuli, then purify the powder by kneading it with waxes and resins to separate impurities from the brilliant blue lazurite crystals. Because this process required both rare material and skilled labour, ultramarine was more expensive than gold.

Painters, therefore, reserved ultramarine for the most sublime subjects. In many artworks, the Virgin Mary’s robes are rendered in ultramarine, signifying her role as Queen of Heaven. The pigment thus combined religious symbolism, aesthetic beauty, and economic demonstration of patronal devotion.

Beyond symbolism, ultramarine also excelled technically. It was chemically stable and resistant to fading, ensuring that its brilliance endures centuries later. When art historians analyse Renaissance palettes, ultramarine consistently emerges as the pinnacle of pigment prestige.

Malachite and Verdigris: The Greens of Nature

Green held complex meaning in Renaissance art, symbolising growth, fertility, and the natural order. Two key sources were malachite and verdigris.

- Malachite: A copper carbonate mineral, malachite produces a soft but rich green when ground. It had been used since antiquity and was regarded as a mineral with protective powers.

- Verdigris: Made chemically from exposing copper to vinegar vapours or corrosion, verdigris yielded a bright, turquoise-green. Initially luminous, however, it suffered from instability, often darkening or fading to a brown hue over time.

Renaissance artists used both, often layering them to achieve varied effects in landscapes and decorative details. The instability of verdigris caused headaches for painters and conservators alike, but its initial brightness kept it in circulation.

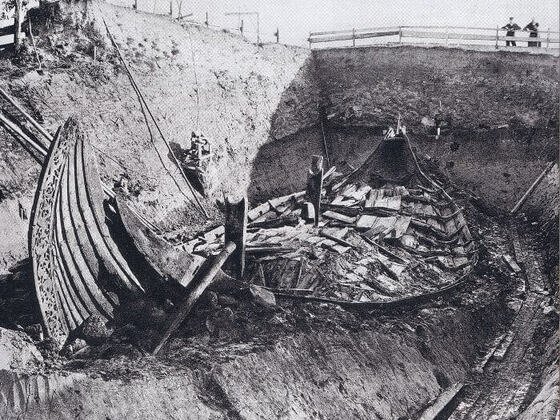

![Pigment analysis of Raphael's masterpiece[7][8] reveals the usual pigments of the renaissance period such as malachite mixed with orpiment in the green drapery on top of the painting, natural ultramarine mixed with lead white in the blue robe of Madonna and a mixture of lead-tin-yellow, vermilion and lead white in the yellow sleeve of St Barbara.](https://gemstonesinsider.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Raphael-Madonna_Sistine_sm.webp)

Cinnabar and Vermilion: The Red of Power

Few pigments matched the visceral brilliance of vermilion, derived from natural cinnabar (mercury sulfide). Cinnabar was mined particularly in Spain’s famed Almadén mines, an essential source of European vermilion.

The alchemical preparation of artificial vermilion, which involves combining mercury and sulfur and heating them until they fuse, also emerged in medieval times. Whether from natural or synthetic sources, vermilion provided a bright, saturated red central to Renaissance iconography.

Red symbolised life, blood, sacrifice, and authority. Artists used vermilion in religious paintings to convey Christ’s passion or in secular works to highlight political power. Manuscript illuminators lavished vermilion on initials, while painters like Titian infused his canvases with its fiery glow.

Yet vermilion carried dangers. Vapours released during grinding and preparation exposed pigment makers to toxic risks, making red a literal price in human health. Still, the allure of vermilion proved irresistible.

Ochres and Earth Pigments: The Timeless Neutrals

Compared to ultramarine or vermilion, ochres may seem humble. Yet these earth pigments, rich in iron oxides, provided an essential foundation of Renaissance palettes. Yellow ochre, red ochre, burnt sienna, and umber offered consistency, affordability, and reliability.

Ochres shaped everything from the warm flesh tones of portraits to the underpaintings of large fresco cycles. Their use also carried a timeless lineage: the same pigments appear in Palaeolithic cave murals at Lascaux, linking Renaissance art to humanity’s earliest creative impulses.

Importantly, ochres harmonised with brighter, rarer pigments. Where ultramarine sang with celestial resonance, ochre grounded the composition in human warmth and earthly tones.

Azurite, Realgar, and Orpiment: Other Rare Colours

Beyond the most famous stones, Renaissance artists experimented with other minerals:

- Azurite: A copper carbonate gemstone that produces a vivid blue colour. It was cheaper than lapis lazuli but often transformed chemically into green malachite over time.

- Realgar: An arsenic sulfide mineral yielding an orange-red pigment. Its instability and toxicity limited its widespread use.

- Orpiment: Another arsenic sulfide, providing a striking golden-yellow hue. Although brilliant, it reacted poorly with many other pigments and posed health risks.

These pigments reveal the Renaissance spirit of experimentation. Painters and pigment grinders constantly balanced colour brilliance with durability, availability, and health risks, producing art that was as much about technical mastery as aesthetic genius.

Crafting Pigments: Alchemy, Art, and Science

The preparation of pigment stones was as central to Renaissance art as the painter’s brush. Workshops employed colour grinders, specialists trained to transform raw minerals into workable pigments. Their methods often resembled alchemical processes: heating, mixing, and separating substances with almost mystical secrecy.

For example, creating ultramarine involved a multi-step ritual. The ground lapis lazuli was combined with wax, pine resin, and gum Arabic, then kneaded repeatedly in a lye solution to extract the precious blue particles. This routine could take days, if not weeks.

The secrecy around pigments reflected not only trade competitiveness but also symbolic resonance. Alchemy regarded colour transformations as metaphors for spiritual refinement. Thus, pigment preparation straddled both science and mysticism, advancing chemical knowledge while preserving ritualistic traditions.

Symbolism and Sacred Meaning of Pigments

For the Renaissance mind, pigments were never just physical. They carried semantic weight:

- Ultramarine = transcendence, purity, heaven.

- Vermilion = blood, martyrdom, passion, power.

- Green (malachite/verdigris) = spring, nature, rebirth.

- Gold and orpiment = divine radiance.

- Earth pigments (ochre, umber, sienna) = mortality, grounding, human existence.

Iconography relied heavily on these associations. Devotional panels used ultramarine for Mary to emphasise her divine role, while martyrs’ robes gleamed red with vermilion. Patrons even issued contracts specifying which pigments artists must use, blending theology and commerce into chromatic choices.

Conservation Challenges of Mineral Pigments Today

Despite their durability, many mineral pigments face challenges centuries later. Verdigris blackens; cinnabar can darken due to light or chemical reactions; azurite slowly shifts to green malachite. Conservators grapple with these changes, balancing the desire for faithful restoration with their ethical obligations to preserve the original material.

Today, museums employ advanced scientific methods, such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF), infrared spectroscopy, and Raman analysis, to identify pigments and diagnose their condition. This union of chemistry and art history not only restores paintings but also preserves knowledge of Renaissance techniques.

Legacy of Pigment Stones in Modern Art and Science

Although synthetic pigments have replaced mainly natural ones, the legacy of pigment stones lives on. Nineteenth-century chemists introduced synthetic ultramarine, cadmium red, and chromium-based greens, creating consistency and affordability. Modern conservation science continues to study natural pigments to better understand chemical stability and degradation.

Meanwhile, contemporary artists have revived interest in natural pigments and grinding stones as a gesture of returning to traditional craft. The pigment stones of the Renaissance remind us that art and nature, chemistry and beauty, are inseparably linked.

Conclusion

The hidden world of pigment stones offers a profound lens on the Renaissance. Ultramarine told of distant mountains and divine purity; vermilion glowed with the power of sacrifice and empire; humble ochre tied the Renaissance to humanity’s oldest artistic instincts. Each pigment carried not just colour but story, linking geopolitics, economy, faith, and science.

By understanding these natural pigments, we glimpse the Renaissance as not only a cultural rebirth but also a geological one: a moment when stones became paint, minerals became meaning, and earthly matter was elevated into eternal beauty.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Renaissance pigments came from both mineral stones (like lapis lazuli, cinnabar, malachite, and ochre) and organic materials such as plants or insects. Artists valued mineral pigments for their brilliance and durability.

Ultramarine was created from rare lapis lazuli mined in Afghanistan. The complex purification process and long trade routes made it incredibly costly, often exceeding the price of gold.

Pigment makers risked exposure to toxic minerals like cinnabar, verdigris, realgar, and orpiment, which contained mercury or arsenic compounds. These hazards made pigment grinding a dangerous craft.

Modern conservators utilise scientific tools such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and Raman spectroscopy to identify pigments, analyse their stability, and preserve Renaissance masterpieces.

While toxic minerals are no longer common, earth pigments like ochres and sienna remain in use. Synthetic ultramarine, cadmium reds, and chromium greens replicate the brilliance of Renaissance mineral pigments safely and effectively.

Ready to Start Your Gemstone Journey?

Don’t wait to discover the world of gemstones! Explore these essential reads right away.

Fascinated by this article and want to deepen your gemstone expertise? Dive into our comprehensive Gemstone Encyclopedia. Here, you’ll discover detailed information about hundreds of precious and semi-precious stones, including their properties and values.

For those interested in the rich cultural significance and fascinating stories behind these treasures, our History section offers captivating insights into how gemstones have shaped civilisations. Or perhaps you’d like to learn more about birthstones?

And if you’re considering gemstones as more than just beautiful adornments, visit our Precious Metal Investing guide. Here you will learn how these natural wonders can become valuable additions to your investment portfolio.